The Boléro Un-Ravel’d

The recently published memoirs of Divine Albaret, Maurice Ravel’s bonne and sister of Céleste1, is a simple and engaging text which sheds light on the genesis of the works of Ravel. Divine used to wait for instructions in the kitchen, intently listening to every noise coming from the living-room in which he composed, whence the title of her book, En attendant/En entendant2.

In the chapter “Birth of the Boléro”, she speaks as follows of its thematic material:

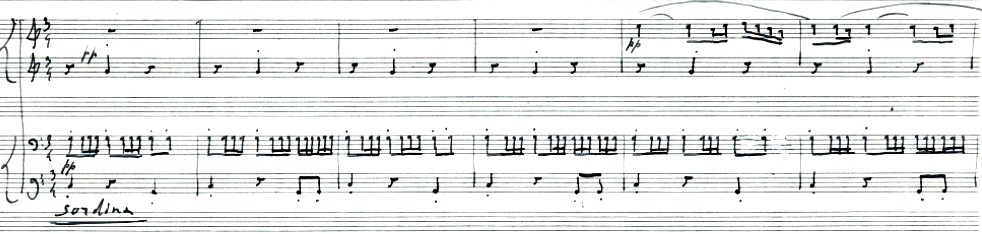

Monsieur composed with great anguish; the conception of each new piece was likened by him to child-bearing pains (les douleurs de l’enfantement), in much the same way as Flaubert suffered when writing. [...] For the Boléro, he was even more nervous than usual, at times pensively pounding his pencil on the piano, at times nervously tapping his foot on the parquet ciré (more work for me), while silently smoking stinking cigarettes. After days and days of frustration, he suddenly snapped to attention, hearing for the first time the rhythmic pattern that his pencil was creating3. This is how the Boléro was born.

Divine then proceeds to tell us how he tried working on this one musical idea he had found, frustratingly pursuing the ideal and elusive perfection, by slightly varying, from version to version, rhythm, orchestration, etc. As anybody who has seen his manuscripts can attest, he was very meticulous: he numbered each new attempt, piling the discarded pages under the lid of his concert grand Pleyel. After his death, that’s where they were found4, and musicologists and owners of publishing houses going broke came to the conclusion that this was the score of an unpublished (single) work of his, not realizing that the last page was the only one he had been pleased with.

As to the title of the work (which nowhere appears on the so-called manuscript), it was suggested to the publishers5 by a friend of Ravel who thought he had heard him mutter this word while playing the [main] theme. Actually, what Ravel had said was ‘‘Beau, l’air, ho?’’ (i.e., ‘‘the melody is nice, uh?’’)6.

Recently, literary critics7, moving from the particular to the general, have advanced a theory, known as cumulisme historique, which aims at explaining the sometimes overbearing repetitiveness in arts and humanities as the accidental rémanence and accumulation of all sketches leading to the completion of an object, as a result of which one sees the whole history of the work rather than just the end product. As supportive evidence of its applicability to other fields such as religion, they bring the so-called neocreationist (or ‘‘post-Darwinist’’) interpretation of the Biblical story of Genesis, according to which God was merely warming up during the first five days for the culmination of His work in Man and Woman, never intending the intermediate results to stay around8

Other striking validations of this new theory are in the musical domain, where it operates both as explanation and prediction (or prescription). For the former, we have Divine´s factual recounting, but also a by now famous analysis of the endless codas of some of Beethoven’s symphonies. For the latter, it is put to use in recording sessions of recent minimalist compositions: they consist of a single take of the theme, to be duplicated as many times as necessary to fill an album of the commercially required length.

Le Miklos, 1985-2021

_________________________

1. Proust’s devoted house-keeper.

2. Sorbonne University Press, 1985, 788pp.

3. This text must have come to the attention of Laurie Anderson, who uses in United States a similar language to describe early breakfast in front of the cereal box: ‘‘And suddenly, for some reason, you snap to attention, and you realize that what you are reading is what you are eating…’’

4. Divine had standing orders not to touch any musical material of his. Parenthetically, she recounts how she would manage to do the dusting sans toucher. Though illiterate, she was a very literal person.

5. Heschig, 2bis rue Vivienne.

6. P. 244 of Divine´s book, op. cit. ‘‘Ho’’ is a common interjection in the Pays Basque, country of origin of Ravel.

7. Esp. French post-structuralists.

8. ‘‘Do you think Leonardo da Vinci, or any other artist, for that matter, would have been very pleased to see his sketches exposed to the public?’’ asks Susan Sontag, one of the more eloquent speakers of this group, in her essay Notes On Outdoor Camping.