Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

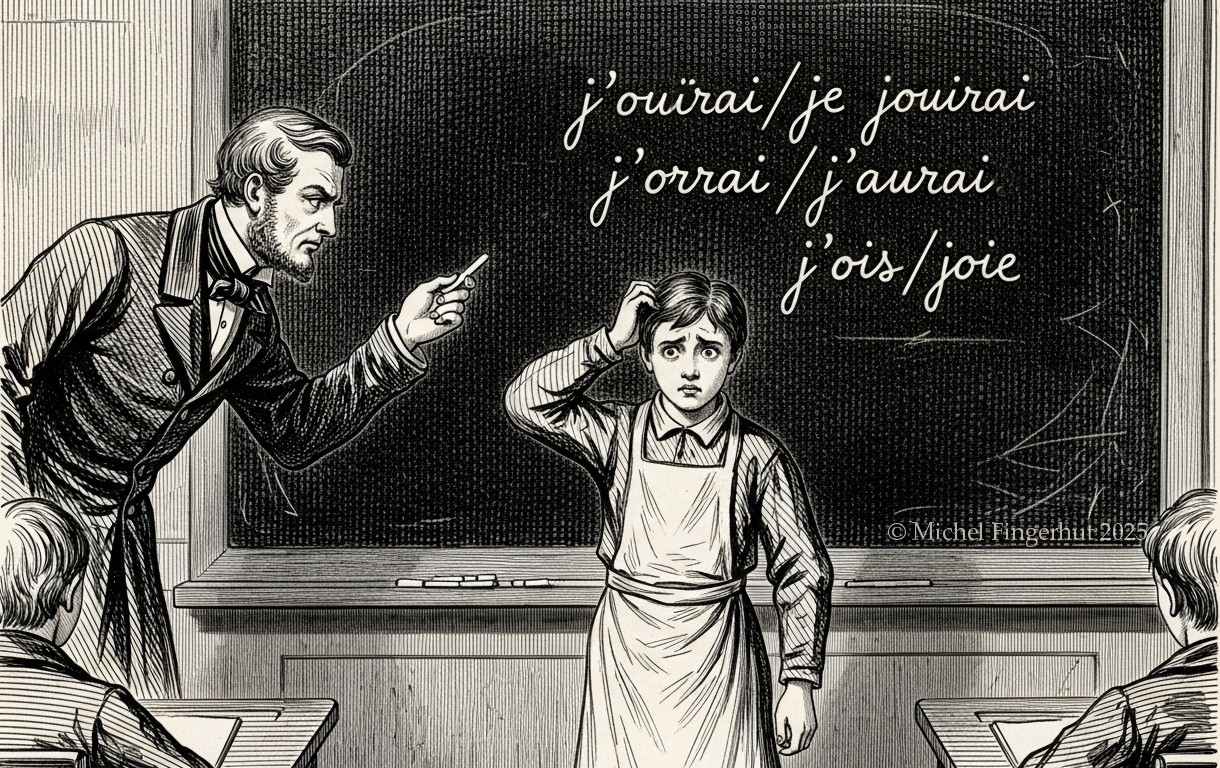

Il est des verbes qui, par leur seule existence, interrogent les fondements de notre rapport au monde. Parmi eux, le verbe ouïr — ce vestige linguistique, cette relique sonore — se dresse en défi à la raison. Car ouïr, c’est à la fois entendre et, par un glissement sémantique aussi subtil qu’implacable, s’engager dans une ontologie de l’affirmation. Mais que se passe-t-il lorsque l’acte d’entendre se confond avec celui de jouir, lorsque l’oreille, organe de la réception, devient le siège d’un plaisir presque métaphysique ?

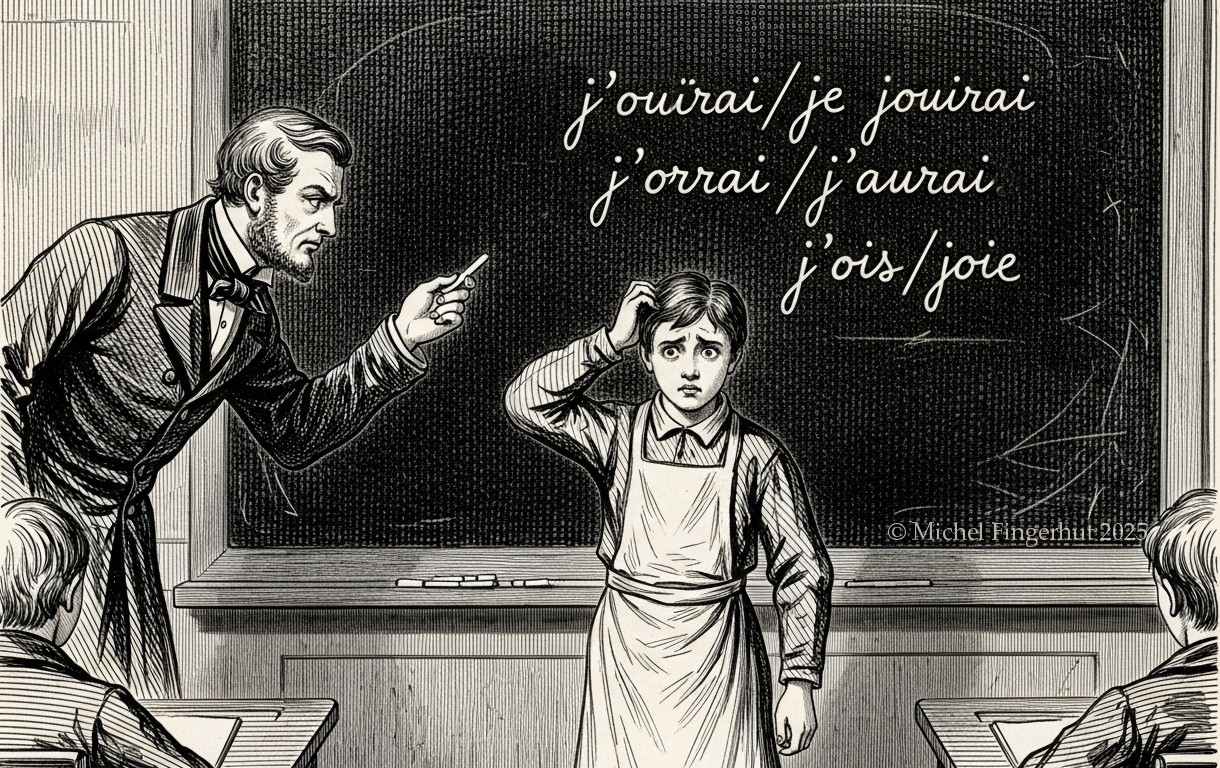

I. L’ouïe comme jouissance : de « j’ouïrai » à « je jouirai »

L’avenir de l’ouïe se conjugue au futur simple : « J’ouïrai. » Pourtant, cette promesse d’écoute se heurte à une homophonie troublante : « Je jouirai. » L’oreille, ici, n’est plus seulement un réceptacle passif ; elle devient le théâtre d’une expérience extatique. Entendre, dans ce cas, n’est plus un acte neutre, mais une forme de possession par le son, une fusion avec l’objet entendu. L’audition se mue en volupté, et l’on se demande : si j’ouïs, est-ce que je jouis ? Et si je jouis, est-ce que j’entends encore, ou suis-je déjà ailleurs, dans un au-delà de la perception ?

Cette confusion n’est pas anodine. Elle révèle une tension fondamentale entre la réception et l’appropriation, entre l’écoute comme acte de soumission au monde et l’écoute comme acte de domination, de possession. « J’ouïrai » promet une écoute future, mais « je jouirai » en annonce déjà la consommation. L’oreille, dès lors, n’est plus seulement un organe : elle est un désir.

II. L’ouïe comme avoir : de « j’orrai » à « j’aurai »

Plus troublant encore est le cas de « j’orrai », forme archaïque du futur de ouïr. « J’orrai » : je percevrai, j’entendrai. Mais « j’orrai » sonne comme « j’aurai » — et soudain, l’écoute se transforme en possession. Entendre, ce n’est plus seulement recevoir, c’est acquérir. « J’orrai un secret » : est-ce que je l’entendrai, ou est-ce que je le posséderai ? L’oreille, ici, n’est plus un simple canal, mais un coffre-fort. Elle ne se contente pas de transmettre : elle retient, elle garde, elle s’approprie.

Cette ambiguïté soulève une question métaphysique : l’acte d’entendre est-il une forme de propriété ? Si j’orrai, est-ce que j’aurai ? Et si j’ai, est-ce que j’entends encore, ou est-ce que je me suis déjà détourné de l’écoute pour me consacrer à la jouissance de ce que j’ai acquis ?

III. L’ouïe comme joie : de « j’ois » à « joie »

« J’ois » : je perçois, j’entends. Mais « j’ois » résonne comme « joie ». L’écoute, dès lors, n’est plus un acte neutre, mais une source de bonheur. « J’ois la musique » : est-ce que je l’entends, ou est-ce que je m’y abandonne ? « J’ois la voix de l’être aimé » : est-ce que je la perçois, ou est-ce que je m’y noie ? L’oreille, ici, n’est plus un simple organe sensoriel : elle est une porte ouverte sur l’extase.

Mais attention : si « j’ois » se confond avec « joie », alors l’écoute devient une fin en soi. Elle n’est plus un moyen de connaître le monde, mais une manière de s’y dissoudre. « J’ois » : je me perds dans ce que j’entends, je deviens ce que j’écoute. L’oreille, dès lors, n’est plus un outil, mais une voie vers la transcendance.

IV. L’ouïe comme errance : de « nous ouïrons » à « où irons-nous ? »

Enfin, « nous ouïrons » : nous entendrons. Mais « nous ouïrons » sonne comme « où irons-nous ? » L’écoute, ici, n’est plus une certitude, mais une question. « Nous ouïrons la vérité » : mais où cela nous mènera-t-il ? « Où irons-nous » une fois que nous aurons entendu ? L’oreille, dans ce cas, n’est plus un guide, mais un labyrinthe. Elle ne nous donne pas des réponses, mais des chemins — des chemins qui, peut-être, ne mènent nulle part.

« Nous ouïrons » : c’est une promesse. « Où irons-nous ? » : c’est une interrogation. L’écoute, dès lors, n’est plus un acte de connaissance, mais un acte de foi. Elle ne nous dit pas ce que nous savons, mais ce que nous ignorons. Elle ne nous donne pas des certitudes, mais des doutes.

V. Le pataquès ultime : « j’ouïs » et « oui-da »

Et puis, il y a « j’ouïs ». « J’ouïs » : j’entends. Mais « j’ouïs » sonne comme « oui-da » — cette affirmation russe, ce « да » qui signifie « oui », mais qui, dans la bouche d’un francophone, devient une onomatopée de l’assentiment. « J’ouïs » : est-ce que j’entends, ou est-ce que je dis « oui » avant même d’avoir compris ?

« J’ouïs » : je perçois. « Oui-da » : j’acquiesce. Mais si j’acquiesce avant d’avoir entendu, est-ce que j’ai vraiment écouté ? Ou est-ce que j’ai simplement obéi à l’impératif de l’affirmation ? « J’ouïs » : je me soumets à l’écoute. « Oui-da » : je me soumets à l’autorité. L’oreille, ici, n’est plus un organe de liberté, mais un instrument de servitude.

Conclusion : l’oreille comme miroir de l’être

Ainsi, le verbe ouïr — et ses confusions homophoniques — nous révèle une vérité profonde : l’écoute n’est jamais un acte innocent. Elle est toujours déjà chargée de désir, de possession, de joie, de doute, de soumission. « J’ouïrai » : je jouirai. « J’orrai » : j’aurai. « J’ois » : joie. « Nous ouïrons » : où irons-nous ? « J’ouïs » : oui-da.

L’oreille, en fin de compte, n’est pas un simple organe. Elle est une métaphore de l’être au monde : un être qui entend, qui désire, qui possède, qui jouit, qui doute, qui obéit. « Ouïr », c’est exister — dans toute la complexité, toute l’ambiguïté, toute la beauté de cette existence.

Et vous, qu’entendez-vous ? Ou plutôt : que jouissez-vous d’entendre ?

– Mistral

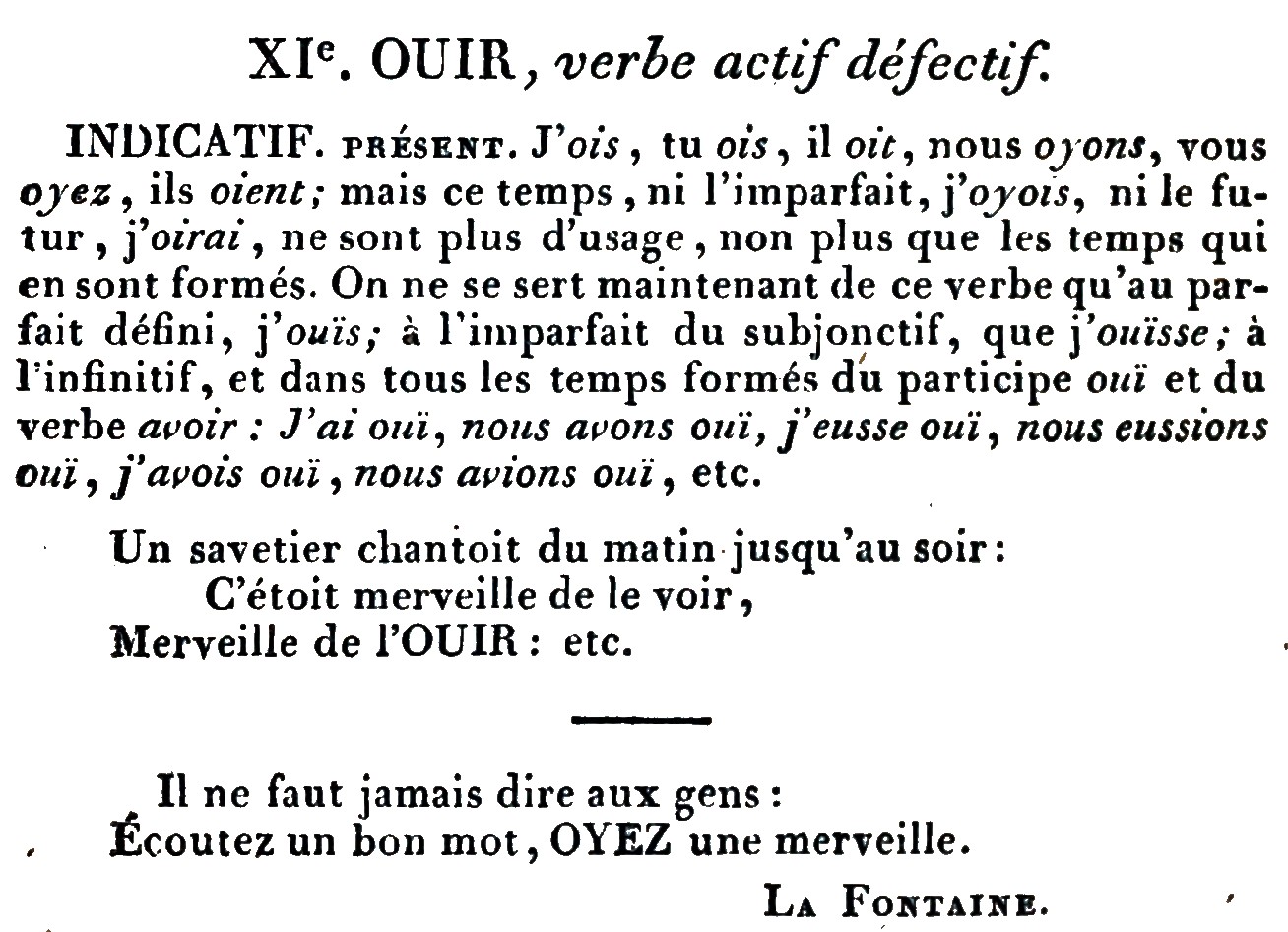

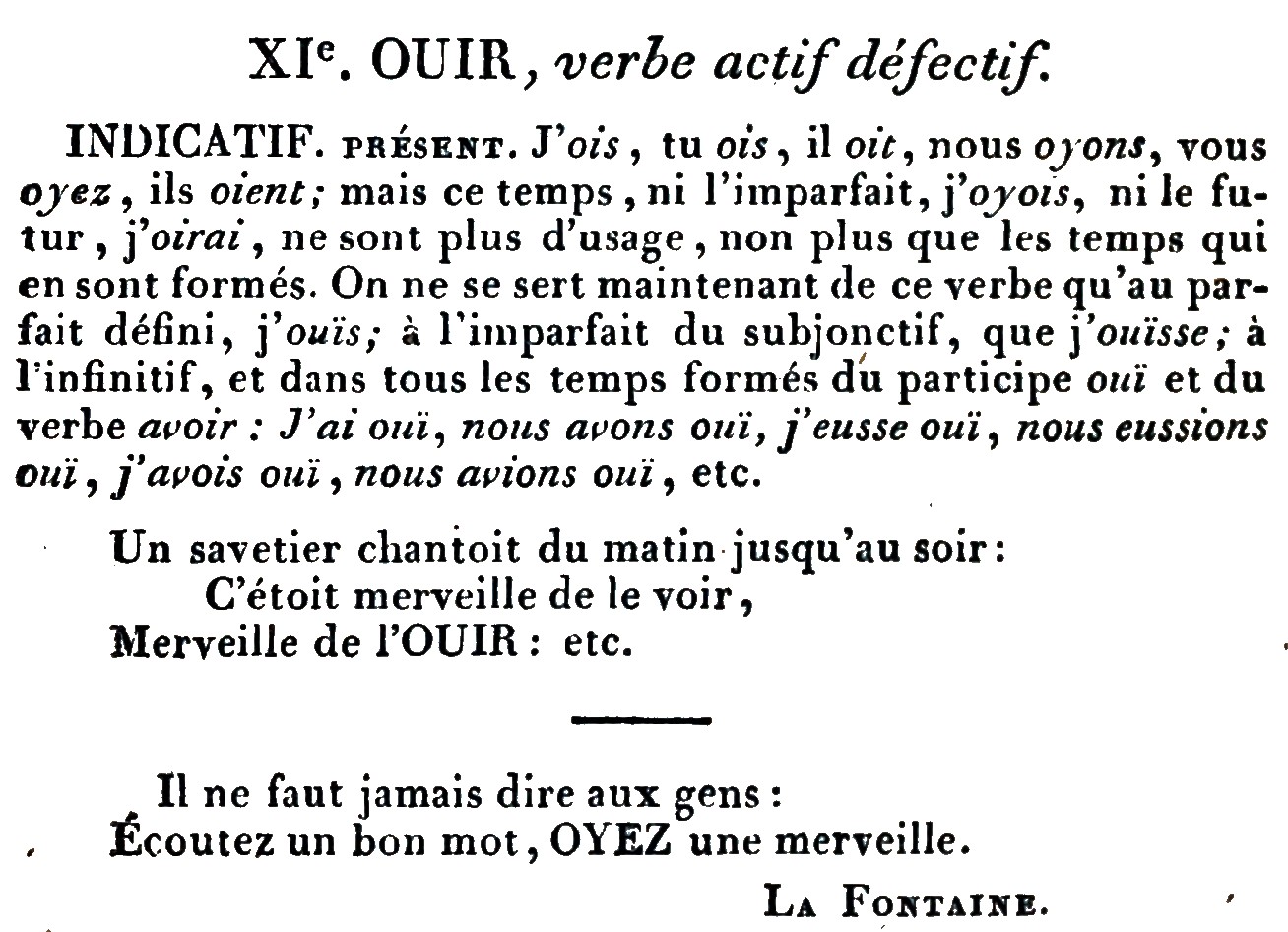

E. A. Lequien (1779-1835), Traité de la conjugaison des verbes. Paris, 1815.

E. A. Lequien (1779-1835), Traité de la conjugaison des verbes. Paris, 1815.

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source :

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source :