Mal traduire un auteur, c’est ajouter au malheur de ce monde

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk.

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk.

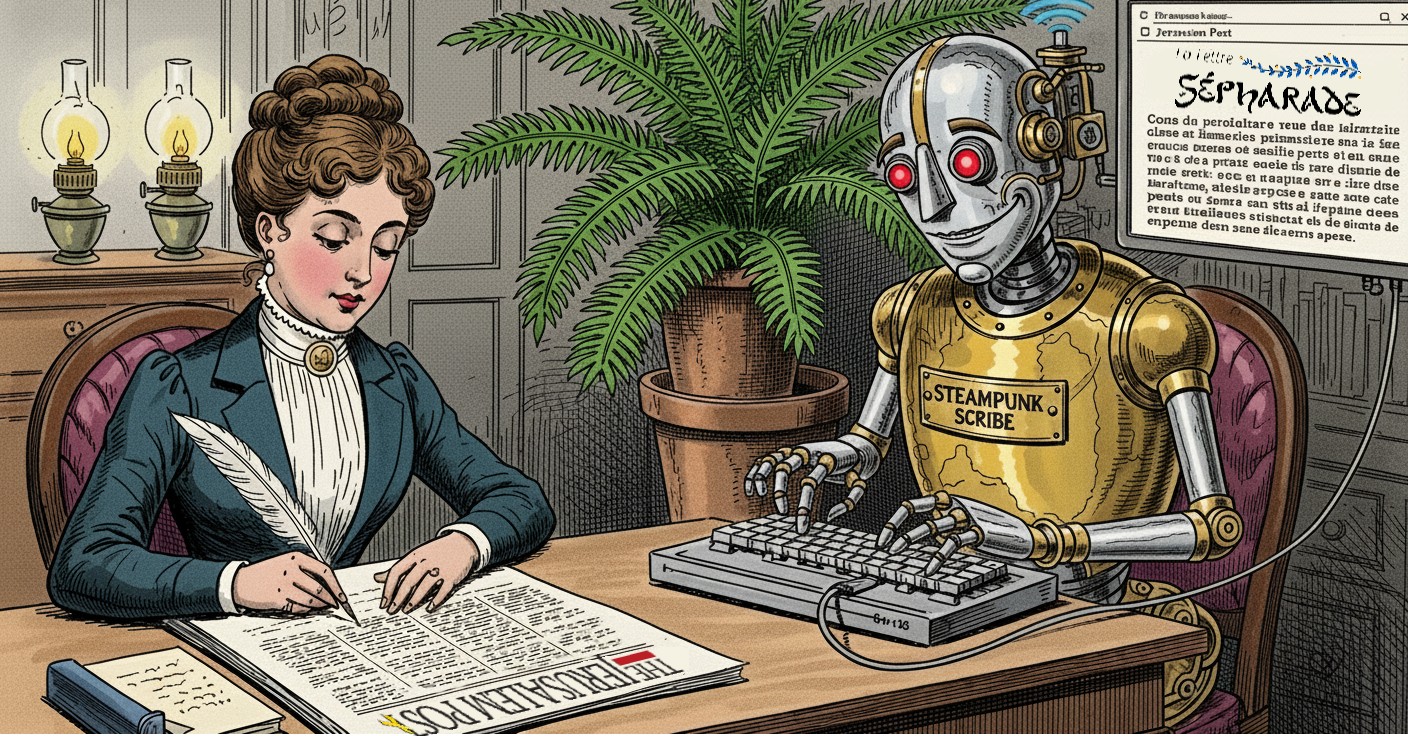

Le blog La Lettre Sépharade a publié, il y a quelques jours, un article intitulé « Le rabbin Jonathan Sacks est décédé il y a 5 ans. Son nouveau commentaire de la Torah fait des vagues en Israël ». En voici le début :

TEL AVIV – Il y a trois ans, l’éditeur basé à Jérusalem, Matthew Miller, a reçu un appel du chef de la plus grande chaîne de librairies d’Israël.

Le directeur général de Steimatsky, Ayal Grinburg, a déclaré qu’il regardait les traductions des œuvres de feu Jonathan Sacks volant des étagères et voulait savoir pourquoi un rabbin britannique se connectait avec des lecteurs israéliens souvent indifférents aux voix extérieures.

Miller, originaire de Brooklyn qui avait vécu en Angleterre avant de s’installer en Israël, a emmené Grinburg pour déjeuner pour expliquer le «phénomène» des sacs, l’ancien chef rabbin du Royaume-Uni. Dans son écriture et ses apparitions publiques fréquentes, les sacs ont amené les valeurs de la Torah sur la philosophie, la politique et les débats éthiques de l’époque. Alors qu’il se battait parfois avec des Juifs à sa droite et à sa gauche, il a tenu une stature comme intellectuelle publique que peu de dirigeants juifs de sa génération pouvaient égaler.

Quel charabia ! Curieux, non ? La suite – en voici quelques extraits – est à la hauteur de ce début :

La traduction est simple et lisible. « Autant les Yea et les Thous », a déclaré Dayan Ivan Binstock de Beth Din à Londres, qui a passé en revue le texte. […]

Au moins trois présidents israéliens et comme de nombreux premiers ministres ont parlé de sacs avec révérence et tiré sur ses écrits. Le chef de l’opposition, Yair Lapid, qui est laïque, a déclaré qu’il était «la seule personne que je serais heureuse d’avoir comme rabbin» […]

Parler avec révérence de sacs (il s’agit évidemment de Sacks) et en même temps tirer sur ses écrits ? Et quant à Monsieur Yaïr Lapid, il ne serait sans doute pas très heureux qu’on dise de lui qu’elle est heureuse…

L’héritage des Sacks Rabbin, dirigé en Israël par son frère cadet Alan Sacks […]

Seize de ses livres ont maintenant des éditions hébreuses […]

«Il était essentiel pour nous de trouver quelqu’un avec l’émotion et la sensibilité à communiquer [his] Message sans perdre sa personnalité »

Comme on pouvait déjà s’en douter, ce « style » abracadabrantesque semble bien provenir de la traduction par une IA hallucinante d’un article en anglais. Et il suffit alors de prendre une expression typique de ce texte, par exemple « trois présidents israéliens », de la traduire en anglais (“three Israeli presidents”), d’y accoler le mot « Sacks » et d’effectuer une recherche en ligne.

Et bingo ! La première réponse mène vers un article en très bon anglais du très sérieux Jerusalem Post (quotidien israélien de langue anglaise, fondé en 1932), indiquant provenir de la JTA (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, ou Agence télégraphique juive, agence de presse internationale fondée en 1917) : c’est d’évidence la source de cette hallucinatoire traduction mot pour (mauvais) mot qui en reprend aussi les illustrations, mais qui n’en cite ni la source (JTA), ni le sous-titrage des illustrations qui en comprennent les attributions.

On remarquera aussi que le nom de l’auteur de l’article en français est celui de l’éditeur de la Lettre Sépharade, alors que l’article original, dont il n’est qu’une pauvre traduction littérale, a été rédigé par la journaliste Deborah Danan.

Pour finir, voici quelques exemples de la source en anglais et du résultat en français :

|

Steimatsky chief executive Ayal Grinburg said he was watching translations of works by the late Jonathan Sacks fly off the shelves and wanted to know why a British rabbi was connecting with Israeli readers, often indifferent to outside voices. |

Le directeur général de Steimatsky, Ayal Grinburg, a déclaré qu’il regardait les traductions des œuvres de feu Jonathan Sacks volant des étagères et voulait savoir pourquoi un rabbin britannique se connectait avec des lecteurs israéliens souvent indifférents aux voix extérieures. |

|

Miller, a Brooklyn native who had lived in England before settling in Israel, took Grinburg to lunch to explain the “phenomenon” of Sacks, the former chief rabbi of the United Kingdom. |

Miller, originaire de Brooklyn qui avait vécu en Angleterre avant de s’installer en Israël, a emmené Grinburg pour déjeuner pour expliquer le «phénomène» des sacs, l’ancien chef rabbin du Royaume-Uni. |

|

At least three Israeli presidents and as many prime ministers have spoken of Sacks with reverence and drawn on his writings. Opposition leader Yair Lapid, who is secular, said he was “the only person I’d be happy to have as my rabbi,” |

Au moins trois présidents israéliens et comme de nombreux premiers ministres ont parlé de sacs avec révérence et tiré sur ses écrits. Le chef de l’opposition, Yair Lapid, qui est laïque, a déclaré qu’il était «la seule personne que je serais heureuse d’avoir comme rabbin» |

Il s’avère en fait que la dizaine d’articles qu’on a testés proviennent tous de deux sites d’informations anglophones — Forward et JTA — ce qui peut être légal (c’est par exemple le cas de beaucoup de sites de presse) mais nécessite non seulement un accord, mais une attribution et une traduction correctes…

Si « l’œuvre de traduction s’inscrit dans le cadre juridique du droit d’auteur en tant qu’œuvre de l’esprit », c’est dû au fait que « La traduction ne saurait être assimilée à un travail mécanique »i, ce qui est pourtant le cas en l’occurrence.

Le titre de ce billet est, bien évidemment, une variante de Mal citer un auteur, c’est ajouter au malheur du monde.

___________________

i Hélène Maurel-Indart. « Traduction, plagiat et autres formes d’atteinte au droit d’auteur ». Histoire des traductions en langue française, XXe siècle, Sous la direction de Bernard Banoun, Isabelle Poulin et Yves Chevrel, Ed. Verdier, 2019. hal-03607740