Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

Cliquer pour agrandir. Source : Whisk

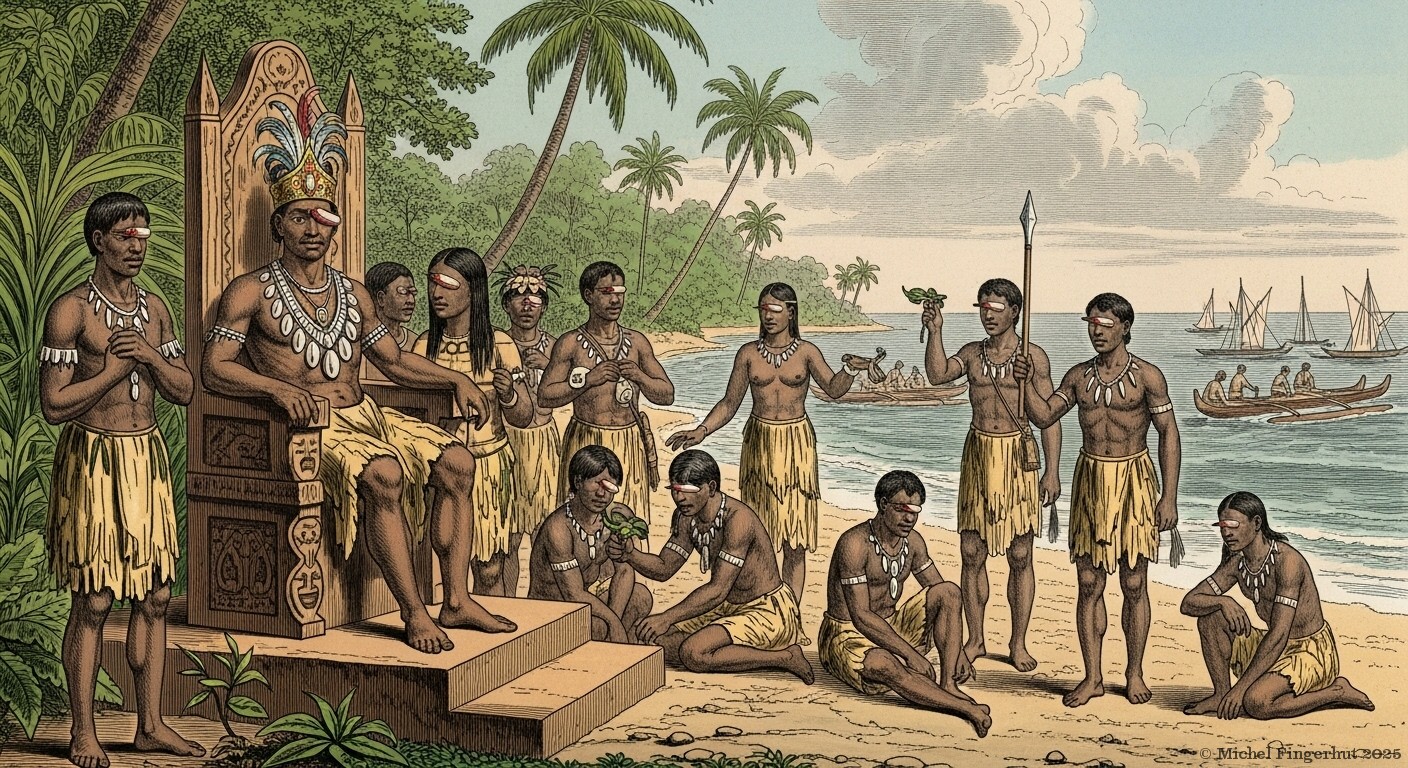

LE PEUPLE BORGNE

«On a fait grand bruit dernièrement de la prétendue découverte d’un peuple qui prend plaisir à se crever un œil pour y voir plus clair de l’autre, suivant ce que disent les bonnes gens qui n’y voient goute. Ce peuple singulier est connu depuis longtemps, et pour le prouver je traduis ce passage du journal d’un voyageur portugais, mort il y a plus d’un siècle ; le nom de cet explorateur des îles de la mer du Sud était Palmaleyra ; son livre a été traduit par le célèbre compilateur Barbaloue, et imprimé en 1729, chez Typhaine, rue des Rats, à la belle image. Je copie servilement la prose de Barbaloue.

« Moi, Palmaleyra, ai franchi la limite jusqu’alors réputée impénétrable des montagnes bleues, et y ai trouvé un peuple singulier. Quelque forte que puisse être la probabilité sur l’ignorance de nos disputes théologiques et philosophiques parmi les habitants d’Ipou-o-Kio-Kio, les paradoxes les plus étranges ont cours chez eux. L’idiome que l’on parle dans ces pays est un dérivé du tartare et du chinois ; tout porte à croire que des malfaiteurs chassés de la Chine pour leurs crimes et éborgnés à cause d’iceux, car les codes chinois appliquent ce genre de pénalité pour plusieurs espèces de méfaits, tout, disons-nous, porte à croire que des malfaiteurs de cette antique nation, après avoir vogué au hasard ont abordé sur cette plage et fondé un état. On présume que, 1° par amour pour l’analogie, 2° par ressentiment de la privation d’un œil et 3° par jalousie contre leurs enfans, dotés plus richement qu’eux par la nature, ils les auront éborgnés sous des prétextes religieux qu’ils ont établi comme base sacrée de toute réunion d’homme. Quoi qu’il en soit de cette supposition, tous les indigènes sont borgnes, et la cérémonie s’y transmet d’âge en âge aussi ponctuellement que chez nous s’est transmise la cérémonie du baptême.

« Après avoir revêtu le costume du pays, qui consiste à se mettre nu comme la main, je m’avançai dans les terres afin d’observer les mœurs, les usages et la forme du gouvernement d’Ipou-o-Kio-Kio. Un système de monarchie absolue, tempéré par les révolutions, régit ces peuplades qui ne sont féroces que par instinct et douces que par fatigue. Le nom de l’Erinouhi, ou roi de ce pays, est Simoié Fadelouboubou, ce qui signifie en langue du pays : tête et gouvernail.

Pendant mon séjour, un homme voulut bouleverser la constitution de l’État : il ameuta la populace, se hucha sur un arbre où l’on pend quotidiennement ceux qui fomentent les troubles, et par un temps d’orage, sous la grêle et le tonnerre, entre des groupes de corbeaux qui attendaient la fin de son discours pour manger les pendus, il s’exprima ainsi :

« Vous tous qui m’écoutez, peuple de borgnes, moi, borgne également par la grâce du fétiche, salut !

« Faisons savoir qu’il nous est advenu une idée, chose rare par le temps qui court, à celle fin que vous ouvriez les oreilles sur la nécessité de garder nos deux yeux.

« En effet, la nature, ce grand prétexte de toutes les idées qui sont révolutionnaires, je le sais bien, mais qui sont aussi excellentes, vous a donné deux yeux originairement pour parer aux accidents qui peuvent vous en enlever un ; et c’est multiplier les aveugles que de crever l’œil gauche, car on peut se dispenser à toute force de naître avec celui là ou l’autre ; mais on veut perpétuer l’infirmité chez nous pour nous mener après cela par le bout du nez. Point de liberté pour nous alors, car dans le royaume des aveugles les borgnes sont les rois. »

L’orateur allait continuer quand deux milles borgnes, armés de bâtons durcis au feu, dispersèrent l’attroupement, saisirent le discoureur et le pendirent. Simoie distribua des récompenses aux justiciers ; on fit des illuminations en réjouissance de la fermeté du gouvernement qui, d’un seul coup, avait éteint une conspiration si dangereuse. Un voyageur qui avait été saisi dans la foule, n’osa pas se dire étranger, parce qu’il connaissait les lois du pays sur l’hospitalité. On lui creva seulement l’œil gauche, et le lendemain il fut admis au baise-pied chez Fadelouboubou, auquel il avoua que rien n’était si joli que le gouvernement de l’érinouhi. Il continua de moucharder les choses avec ce léger désavantage sur les mouchards de nos pays civilisés,» qu’ils ont de plus un œil artificiel dans leur poche sur un papier à vignettes, et qu’il n’en avait qu’un assis à la droite de son nez.

— Le Figaro, 1er avril 1827

_________________

Click to enlarge. Source : Whisk

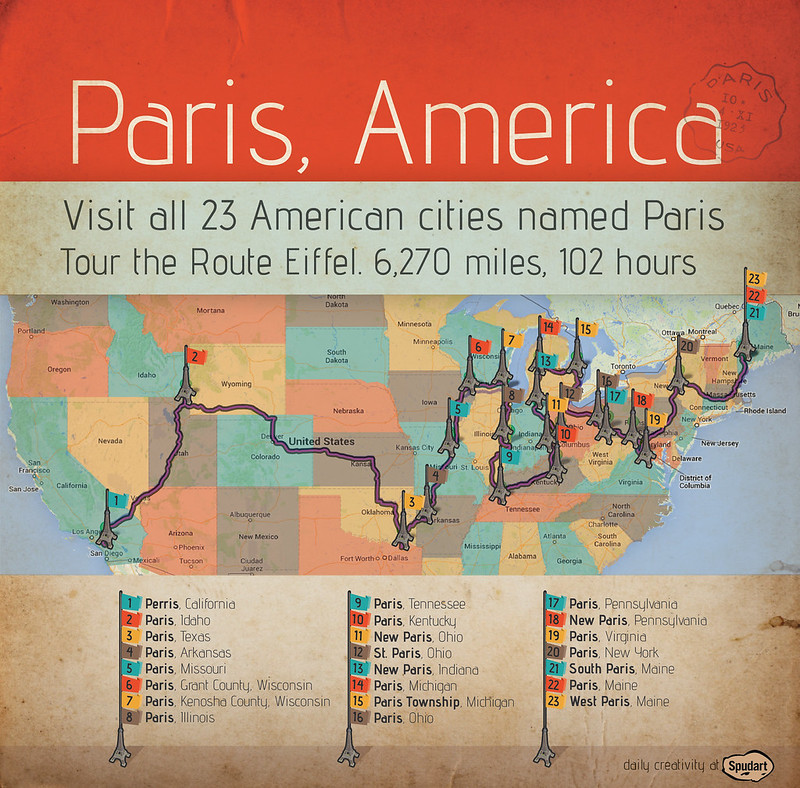

Click to enlarge. Source : Whisk (New Mex.), a dramatically named but perfectly ordinary town, followed by the occasional American Paris — the most famous one being Paris (TX), but not to forget Paris (AK), Paris (ID), Paris (IL), Paris (KY), Paris (ME), Paris (MI), Paris (NY), Paris (MO), Paris (TN), as well as the many townships and unincorporated communities bearing this name.

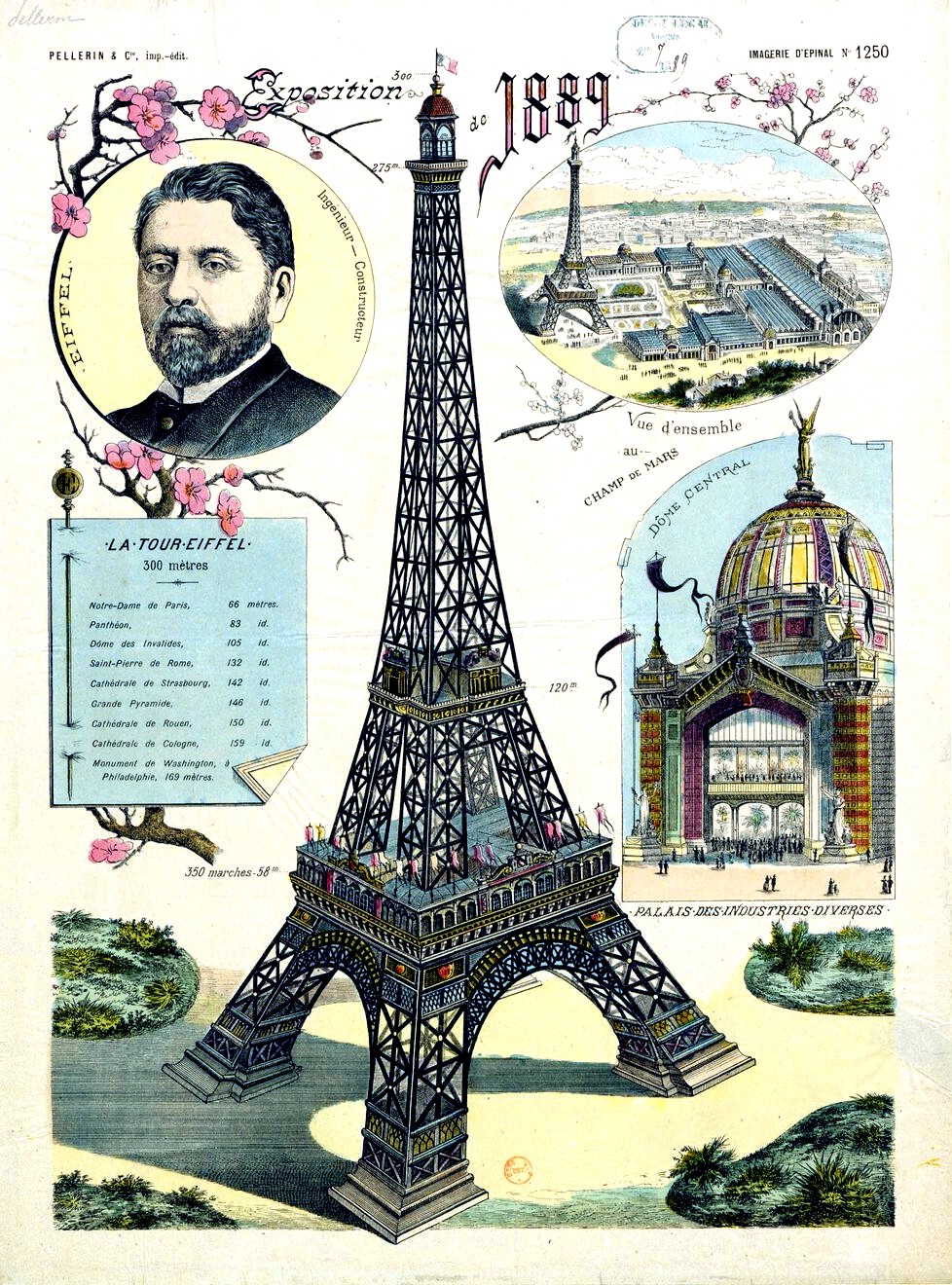

(New Mex.), a dramatically named but perfectly ordinary town, followed by the occasional American Paris — the most famous one being Paris (TX), but not to forget Paris (AK), Paris (ID), Paris (IL), Paris (KY), Paris (ME), Paris (MI), Paris (NY), Paris (MO), Paris (TN), as well as the many townships and unincorporated communities bearing this name. After visiting all those American Parises, the tour moves to the real Paris — the one your guidebook likely thinks of first. Don’t forget to visit its street bearing the shortest name, Py. Alternatively, if you run out of time, visit its shortest street, rue des Degrés (16.4 ft).

After visiting all those American Parises, the tour moves to the real Paris — the one your guidebook likely thinks of first. Don’t forget to visit its street bearing the shortest name, Py. Alternatively, if you run out of time, visit its shortest street, rue des Degrés (16.4 ft). ChatGPT map of the above tour… Only Å is correctly located.

ChatGPT map of the above tour… Only Å is correctly located.