The vampire cat

“Because the Cat is the emblem of the time-honoured ideal of Virgin-Motherhood, the Egyptian Great Mother Goddess, variously invoked as Isis, or Atet, or Mout, etc., as time and place might decree, was constantly represented as assuming feline form.” — M. Oldfield Howey, The Cat in Magic and Myth, 2003 reprint of The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic, 1930.

“Hebrew folk-lore informs us that the Semitic witch-queen Lilith was Adam’s first wife, but that she refused to give him her obedience and flew away, later becoming a vampire. She still lives, and assumes the form of a huge black cat named El Broosha, when she seizes the new-born human babe that is her favourite prey, and sucks its blood.” — Ibid.

From the scarab, the snake and the bee to the dolphin, the monkey or the elephant, animals are so fascinating in their resemblances to, and differences from, man that they are more often than not endowed with various kinds of extraordinary intellectual faculties as well as with natural and supernatural powers ranging from the evil to the useful and the ideal, and thus play key roles in religious, mystical and day-to-day symbolic systems.

Even when domesticated they may keep this aura (which may actually be a good reason to have such an animal at home). This is the case of the cat, which, as Rudyard Kipling has so justly told us, always stays on the wild side. Inscrutable, unpredictable, sensuous and playful, this agile and ferocious hunter’s phosphorescent eyes cast a definitely mysterious light. No wonder it is considered in quite ambivalent, and sometimes contradictory, ways, as the titles of the chapters of Oldfield Howey’s book indicate: Witches in Cat Form, The Cat and Transmigration, The Cat in Paradise, Vampire Cats, Cat as Omens of Death, Clairvoyant Cats, The Cat as Phallic Symbol… and last but not least, The Cat’s Nine Lives.

And so even in afterlife: in Japanese lore, where it also holds both positive and negative places, “the soul of a dead cat (…) can take possession of a human body, speak through its mouth and kill it” (T. Volker)

An 1871 publication was probably the first one to acquaint the West with the legends of Japan: Tales of Old Japan, by Algernon Freeman-Mitford baron Redesdale (who had been second secretary to the British legation in Japan) brought to (European) light the famous story of the Forty-seven Rônins. But it also included tales regarding the supernatural powers of animals, as the author writes: “Cats, foxes, and badgers are regarded with superstitious awe by the Japanese, who attribute to them the power of assuming the human shape in order to bewitch mankind. Like the fairies of our Western tales, however, they work for good as well as for evil ends.”

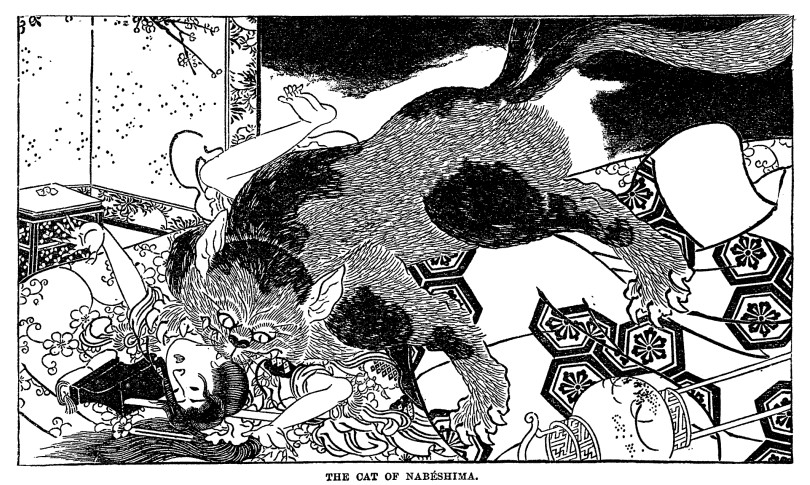

The first story he brings in this section is that of the Vampire Cat of Nabéshima: a black cat takes the shape of a splendid young woman it has just strangled, and sucks the life-substance of her male lover at night when he’s asleep (no wonder one of the symbolic aspects of the cat is sexual, as is the above illustration taken from that book). Several versions of the tale came to us later (including one in Volker’s paper), of which we selected the earlier ones and put them side-by-side so as to provide for an easier comparison: Mitford’s 1871 tale published in the UK, followed by a 1879 relation of Maurice Dubard in French, then by F. Hadland Davis’s version published in the US in 1913, and last the tale as related (in French) by Félicien Challaye in 1933.

While the first and third versions were published in a collection of tales for grown-ups, the two other books are different in nature. Dubard was a French marine officer who spent some time in Japan while on duty, learned Japanese and was fascinated by the “beautiful eyes and cute faces” of the women there (French men will always be French, n’est-ce-pas). His book, Le Japon pittoresque, describes the country, its inhabitants, its culture, its history and its legends, and it is in this context that he brings his own version of the tale of the cat: it is much more “voluptuous” (to use one of his many qualifiers) than the other ones – it is the only one which almost explicitely describes the circumstance of the “life-draining” as effected by the woman-cat –, and, in the end, the evil woman-cat manages to escape the ultimate punishment (an apt conclusion for l’éternel féminin). Apart from his distinctive style, the story differs in this and a couple of other details from Mitford’s, which is circumstantial evidence that he must have had another source: there is no mention of a wife of the prince but only of a favorite (that may just be an omission), the hero is called here Ho-Soda while in all other versions it is Ito-Soda (could it be just due to a transcription error due to the similarity of H and It?), and, more importantly, there is a mention of the double tail of the cat, a significant detail (see again Volker).

Challaye’s story appeared also in a collection of tales, but this one for children: it is part of a famous series of books, Contes et légendes de…, published by Fernand Nathan in the 1930s, then again in the 1960s and 1970s. Here, the Prince has a legitimate wife (even though she barely makes an appearance, as was the case in the French royal court before the French revolution…), and, in contradistinction with the other versions in which the cat manages to escape (and is or isn’t killed later), it is slain on the spot by the valorous servant soldier. Morals are preserved.

We’ll depart here with a smile – the Cheshire Cat’s, naturally.